For me it was a no-brainer to choose Paper VIII for one of my FHS options. It felt like its hugely broad range encompassed all the areas of German literature I was most interested in, and whilst I’m sure the earlier papers hold a huge amount of interest too, doing Joint Honours meant I was effectively choosing one period paper, and Paper X. It’s a very popular paper, so I’m not going to try to sell it as a whole, but what I do want to do is show some of the diversity within it, focusing on the topic of fairy tales which you may well do an essay on when you’re covering the Romantic era.

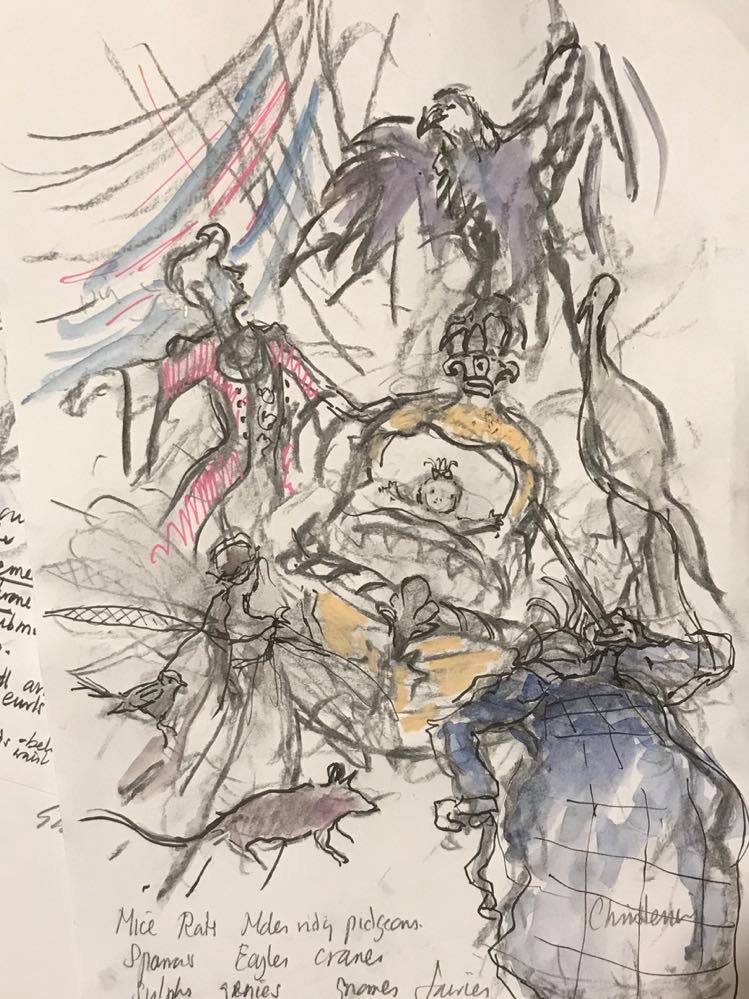

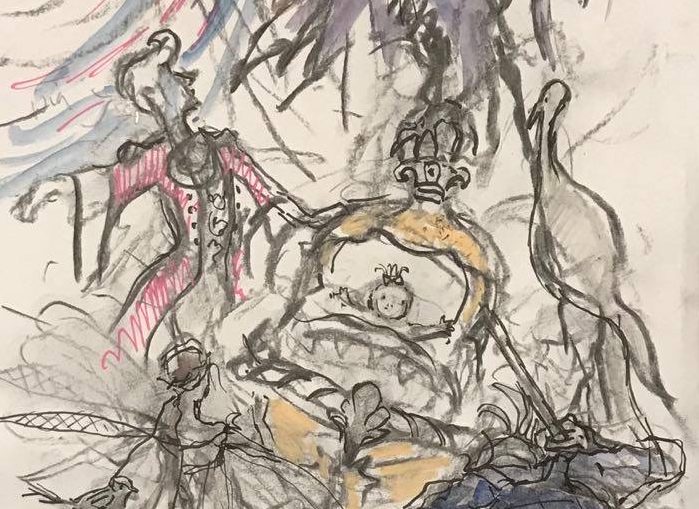

For that essay, I was given a reading list of E.T.A. Hoffmann, Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis – all originators of the Kunstmärchen, a more “literary” approach to the fairy tale – and on the other end of the spectrum, the folk tales of the Brothers Grimm, who allegedly went round little idyllic German villages collecting tales that had been passed down orally over the ages from farmers, country maidens and shepherds. Whether that’s actually how the tales originated is a matter for another time. But chances are, you’ll be given the same reading list, or at least a similar one.

Fairy tales do not stop there!!!!!!!

Forgive the unnecessary font change, but this is something I wish I’d known when I was writing that essay. In the nineteenth century alone, some four hundred women writers published over seven hundred fairy tales and books of fairy tales in the German-speaking world. In fact, the publication of fairy tales began with the conteuses in French literary salons in the seventeenth century, when women used this genre to engage in social and political discourse. So why do we think of the Märchen as a male-dominated genre?

The popularity of the fairy tale in Germany actually began with the success of an anonymous writer – Benedikte Naubert – who wrote more than fifty novels, including the four-volume work Neue Volksmährchen der Deutschen (1789–1792), and who inspired not only many other women writers, but also the Grimm brothers, Tieck and Brentano. Fairy tales proved to be a tried and tested means of entering the public literary realm, since at the time, entertaining fiction, poems, fairy tales and instructive texts on how to bring up children were the only genres considered suitable for women. Recent studies also show that from 1808 to the 1830s, more than fifty women’s stories contributed to the Grimms’ collection. Furthermore, in the early 1800s, new typographical developments were offering more and more opportunities for women to become not merely passive consumers of literature, but active producers in the role of editors and authors. These developments enabled ever increasing numbers of newspapers, journals, magazines, almanacs and, most importantly, paperback books to be printed and shared among the German market. Between 1800 and 1820 around a third of the fairy tales in this paperback form were written by female writers. The fairy tale served as a kind of invisibility cloak, under which women writers could somewhat more inconspicuously confront the issues of their time, a time when women were striving for emancipation, equal rights and equal opportunities. The genre of the fairy tale allowed them to explore alternative realities and subtly criticize patriarchal values and conventions, such as the importance of marriage and the denial of education to women.

Yet reading lists so often repeat this fallacy that the Märchen was a male-dominated genre, and this links into a whole wider issue of literary canons being dominated by men. Unfortunately, reading lists for papers are often handed down without a huge amount of editing being done to account for new research (unless it’s a particular specialist area of your tutor), and these fairy tales written by women have only really come to light within the last ten years. But one thing to know at Oxford is that tutors are always, always happy to talk to you about different texts you’ve found and want to incorporate into your essays. It’s the hall-mark of the so-called ‘no defined syllabus teaching’. And if you come to them with some fairy tales written by women from the period, I wouldn’t be surprised if the following year you’d find they’d be added onto the reading list. I discovered these women’s tales after I’d covered the period in my course, so please do this for me! Tell your tutors about these stories. Discuss with them how they fit into, but also critique the broader fairy-tale tradition. So I’ll finish with my own (very small) alternative reading list:

Shawn C. Jarvis and Jeannine Blackwell (eds. and trans.), The Queen’s Mirror: Fairy Tales by German Women, 1780-1900 (University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, and London, 2001) – this is a book of translated fairy tales, the following publication came about because German readers asked for a similar anthology in the original German, since so many of these fairy tales are out of print or unavailable in libraries.

Shawn C. Jarvis (ed.), Im Reich der Wünsche. Die schönsten Märchen deutscher Dichterinnen (C. H. Beck: Munich, 2012)

Eve Mason, Queen’s

NB. For anyone who’s particularly interested, as well as providing the original German for many of the tales in The Queen’s Mirror, Im Reich der Wünsche includes six newly-discovered tales, five of which I’ve translated over my year abroad. I started off publishing them on a blog, which you can find here (https://feministfairytalesingermany.blogspot.com/), but then decided to self-publish them in a book, so watch this space for that!